US aluminium tariffs: How quickly can the domestic market adapt?

Opinion Pieces

21

Jul

2025

US aluminium tariffs: How quickly can the domestic market adapt?

US aluminium consumers will likely see additional costs, though efforts are underway to increase domestic primary production and use of tariff-exempt scrap.

Since President Trump returned to office in January 2025, the world has faced an ever-changing landscape amid a slew of new US tariffs, with implications across the global economy.

This has and is prompting a reassessment of international trade relationships and economic strategies across the world. These tariffs are threatening lower economic growth, with entities such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank having reduced global growth forecasts for 2025.

This, in turn, will likely restrict demand for commodities and curb prices and investment. Higher import prices in the USA will also raise costs across a wide range of end-use sectors.

On 10 February 2025, under the Proclamation 10895 (Adjusting Imports of Aluminum Into the United States), the US President announced plans to reinstate a 25% tariff on imports of aluminium articles and derivate aluminium articles (as well as steel) into the USA, applicable to imports from all countries as of March 2025, including from its major supplier, Canada.

President Trump also stated that reciprocal tariffs would be announced on countries that tax US imports. By early June 2025, this tariff rate had been doubled, increasing from 25% to 50% for these same aluminium products.

US aluminium import reliance under the spotlight

In the interim, President Trump has announced his first post-tariff agreement with the UK. The US-UK Economic Prosperity Deal was agreed in May 2025, and includes clauses to reduce tariffs on aluminium; however, this will be on the basis that trade complies with strict American security requirements. However, this is unlikely to impact primary aluminium trade flows given that the UK accounts for less than 0.1% of the USA’s unwrought aluminium imports.

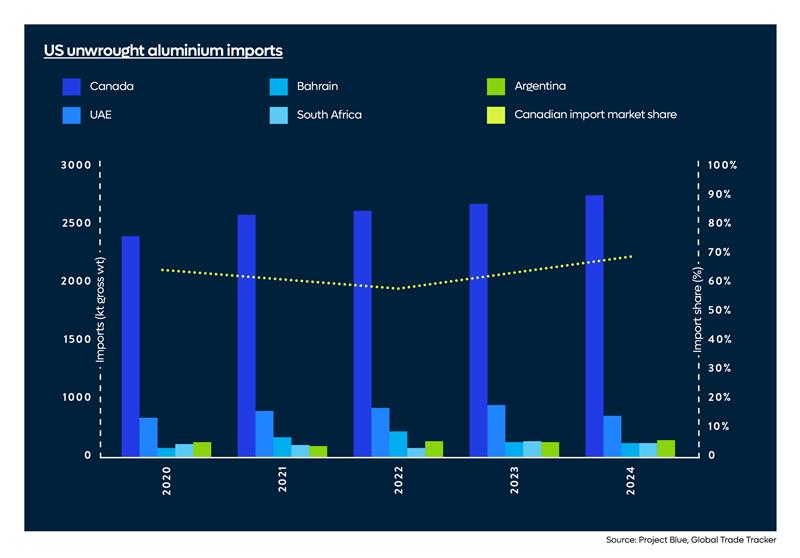

In contrast, the USA is heavily reliant on imports of unwrought aluminium (and steel) from Canada. In 2024, the USA imported around 2.7Mt of unwrought aluminium from Canada and, over the five years, US import reliance on Canada averaged 64%.

The next largest importer into the country is the United Arab Emirates (UAE), accounting for 10-15% of the total, with Bahrain, South Africa and Argentina as the remaining three of top five imports, accounting for ~4% of total imports between 2020-2024.

The assumption is that these higher tariffs will lead to investment in new primary aluminium smelting capacity and in downstream aluminium manufacturing. However, the addition of new smelting capacity is not an immediate solution and will require a considerable amount of time to implement. In the interim, consumers of unwrought primary aluminium and those derivative aluminium products that are subject to these import tariffs will face higher costs, which could, in turn, lead to fewer jobs in the domestic manufacturing sector.

In May 2025, Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA) announced that it plans to develop the first new primary aluminium production plant in the USA; however, it is unlikely to come into production before the end of 2026. The plant is expected to have a production capacity of 600ktpy, which will significantly increase aluminium production in the USA which stood at ~700kt in 2024. The company’s challenge, however, will be its ability to finalise a competitive long-term power supply agreement (spanning 10-20 years) amid competition from the likes of tech firms and data centres, as well as agree on State and local investment incentives and tax credit arrangements, according to an EGA press release in May.

This investment would help bolster domestic primary aluminium production and reduce the USA’s dependence on imports which would also support the downstream aluminium supply chain by reducing dependence on Canada for liquid aluminium. Although this is a step in the right direction, the additional 600ktpy falls well short of the USA’s circa 4Mtpy of primary aluminium consumption. This is in addition to the 2Mtpy (gross weight) of scrap that is imported into the country to meet the needs of end-use sectors ranging from automotive to aerospace and construction to packaging.

Will aluminium trade patterns be redrawn?

Although the tariffs have supported aluminium prices, the key change that has been seen since President Trump doubled the levy on imported aluminium and steel from 25% to 50%, has been the sharp rise in the US Midwest premium. Since the start of 2025, the LME aluminium duty paid Midwest Premium (Platts) has more than doubled from an average of US$525/t in January to an average of US$1,440/t in July (to-date), raising the cost of aluminium for semi fabricators. This increase is subsequently passed on throughout the supply chain, with many already facing additional import tariffs on parts and components which would in turn lead to additional costs for the end consumer.

Other aluminium-focussed sectors, such as the US beverage can industry, are in the meantime looking to reduce costs by increasing their use of recycled aluminium, which is exempt from the 50% tariff on aluminium and steel. However, this plan may yet face some challenges if other countries impose tariffs on their exports of scrap into the USA. In the meantime, those countries subject to the US tariffs, such as Canada, will look to other markets for their aluminium products.

The reality is that the USA is unable to rapidly increase its domestic primary aluminium smelting capacity nor its domestic manufacturing capacity to replace the imported raw material and aluminium components and semis fabricated products in the short term. This will mean that consumers will face higher prices. There is also the risk that the higher domestic prices would erode manufacturing companies' margins. The US automotive sector is particularly vulnerable given the range of tariffs across both upstream and downstream value chains.

Co-authored by Ntebatse Rachidi & Eleni Joannides